In this film inspired by a true story, Wing Chun martial arts master Ip Man (Donnie Yen) and his family are moving from Foshan, China, to Hong Kong, where Ip aspires to create a school so that he may teach his fighting techniques to a new generation. However, he finds resistance from an asthmatic Hung Ga master named Hong Zhen Nan (Sammo Hung). Soon, Ip is drawn into a treacherous world of corruption as well as a fateful showdown with a merciless boxer known as the Twister (Darren Shahlavi).

(Source: Rotten Tomatoes)

Thanks to Netflix streaming services, I am able to revisit old films and “Ip Man 2” (2010) has been a delight to watch again – and now to write about. At this point of writing, the “Ip Man” series has been concluded and although I have yet to watch the final series in the franchise (i.e. “Ip Man 4”), I would say hitherto “Ip Man 2” is my favourite (with it also amassing 6 wins and 10 nominations in film awards).

Certainly, it has lived out to its expectation of an action-martial arts movie with not just believable fight scenes set in an array of settings (from the rooftop to a fish market to a boxing ring) but also choreography that is creative, fresh but also true to the varied Chinese martial art forms (the table duel scene between Ip and the other kung fu masters comes especially to mind here). In short, the quality and quantity of kung fu action in this film will undoubtedly satisfy – at least – lovers of kung fu cinema, but if you are not one, there remains still another reason to watch and that is its heart.

“Ip Man 2” remains one of the few movies that inspires me to be a better person, and it achieves that through – no surprise here – Ip, the protagonist, as a model of mercy and respect (among other virtues of admiration such as his simplicity, modesty, prudence, and sincerity).

“To say that a person is merciful, is like saying that he is sorrowful at heart (miserum cor), that is, he is afflicted with sorrow by the misery of another as though it were his own.”

– Thomas Aquinas

How was Ip portrayed as merciful? There are quite many examples in the film ranging from the trite – in his aiding of the ailing laundry lady to hang out laundry; in his concession to his disciples’ demands to postpone paying their fees due to financial strain – to the unexpected, particularly in his lenient dealings with his retaliatory disciples who ended up costing Ip his martial arts studio place.

I must admit that I was taken aback as to how Ip dealt with his blameworthy disciples after the ruckus. Most of anyone (as I would expect) under Ip’s shoes would have reacted angrily, lashed out, and possibly evicted his disciples for causing an important part of his livelihood to be lost – not least, for their foolish acts. But instead Ip, sensing his disciples’ regret, gently dealt with them, only requiring them to transport his fighting equipment from the studio to his house.

Is that merciful act of Ip rather ‘foolish’ and was it even effective? Was he being too merciful to the extent of being soft and thus open to being taken advantage of?

Well, surely Ip or anybody could be taken advantage of for his mercy but also consider this: mercy shown-sown could also win, soften and mould the hardest of hearts (as with the case of Shun Leong, Ip’s charismatic but troublesome lead disciple), enoble, and also in turn merit mercy for ourselves (“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy” teaches Jesus of Nazareth).

Shun Leong apologising to Ip Man in a scene (Photo capture)

But what of respect?

“Respect for the human person proceeds by way of respect for the principle that everyone should look upon his neighbor (without any exception) as another self, above all bearing in mind his life and the means necessary for living it with dignity.”

– Catechism of the Catholic Church (no. 1931)

Two scenes in particular stood out for me in the exemplification of respect in Ip.

The first is the Ip-masters duel where the dignity of the competitors are upheld through bows (with the martial salute), formal addresses (“___ shi fu”, “Qing”), and deferential behaviour (“Thank you for letting me win”; not displaying excessive joy upon victory). The etiquette evinced in the Ip-masters duel is beautiful to witness no matter of it possibly being labelled as “old fashioned” or “overly formal” – no, courtesy and formality has its place and function in promoting respect that is both beautiful and needful (consider that rules not only prevent disorder but also shape character). Incidentally, the scene also led me to think of other such analogous display of respect present in other sports such as Sumo Wrestling, and tennis (Roger Federer‘s restrained behaviour in the Wimbledon locker room with Andy Roddick in sight come to mind here) which are pleasing to behold and hear about.

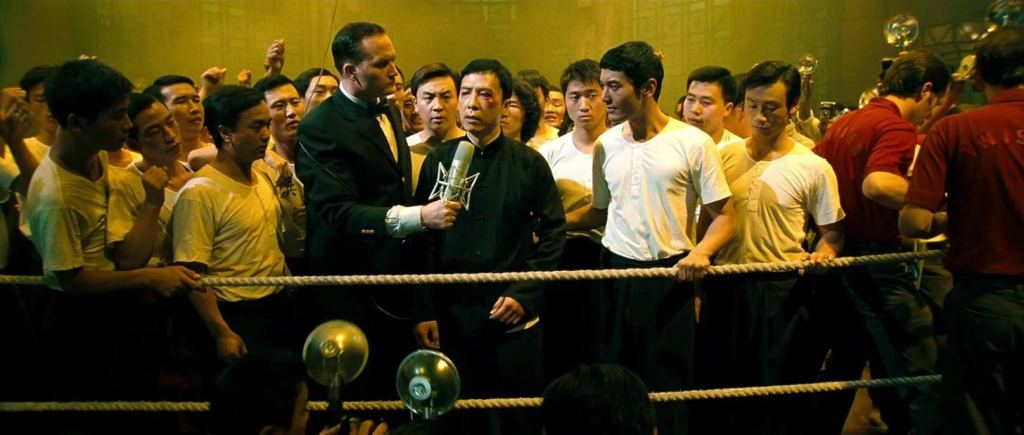

The other scene has to be the closing fight-and-speech sequence of Ip’s battle with Twister where respect (and also mercy) was beautifully expressed in deed (not annihilating Twister as the now-defeated boxer had previously done to master Hong) and in word:

Ip making his speech after the win against Twister (Image Source: IMDb)

“By fighting this match, I’m not trying to prove that Chinese martial arts is better than Western boxing. What I really want to say is though people may have different status in life, everybody’s dignity is the same. I hope that from this moment on, we can start to respect each other.”

Mercy and Respect,

Though “soft” as they look,

More than muscles and brawn,

Are stronger yet still.

To break hard hearts,

And to offer respite,

To enoble others,

And to keep the peace,

Are all up for grabs,

To all and at once.

Will you thus join,

in the prevails of both,

Simple yet strong,

Mercy,

Respect.

*Featured Image Source: blu-ray.com